In 1954 Francois Truffaut (The 400 Blows) published an iconic essay entitled, “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema.” This essay was an attempt to describe what we now call the, “auteur” theory. Initially this theory was (in general) the idea that the director had a vice grip on all of the creative decisions encompassing a film. They were the authors of the story—visual and aural.

This theory, one that gives the power of the story to the person telling it, harkens back to days when stories were communicated across fires—never written down and only communicated via word of mouth. By the time the story was told twenty times, the main character could evolve from a simple moral authority or leader into a God.

Theseus of Athens’ accounts of slaying the Minotaur may have been based in reality (Bulls were important creatures on the Isle of Minos and the Palace of King Minos was maze-like) but after the character of Theseus was bloated to extraordinary proportions, what character are we actually left with? A Hero that spoke with the Gods and defeated supernatural beasts. This game of cross-generational, “telephone” acts as a method of legend creation that spawned tales like the Odyssey and the Iliad. This is also what is at the heart of Pablo Larrain’s wildly original biopic regarding Pablo Neruda.

A Chilean himself, Larrain understands the importance of Pablo Neruda to his country more than most. In fact he’s dealt with political material before in his wonderful handling of Chile's eponymous, "NO" vote to overthrow the military regime of Augusto Pinochet, in the film, “NO.” Neruda was at one time, “the most important communist in the world.” He was a man that stood for thousands, or millions of Chileans that supported the communist party and unions while the Quasi-Fascist regime of Gonzalez Videla (a man Neruda regretfully helped elect) imprisoned and murdered dissenters. Eventually Neruda was impeached from his senate position and was forced underground, running from the government and police to avoid imprisonment and perhaps, death. His time in hiding, and his escape to Europe is documented in his famous Nobel Prize Speech which can be found here.

But it would be a disservice to say that this is a political film. This is a fact that Pablo Larrain clearly defines by setting one of the only outwardly political moments of the film in a bathroom (A possible joke). Political rivals scorn Neruda while he relieves himself at a urinal.

In this same scene a fellow senator shouts epithets at Neruda then finishes, “Are you Neruda, or aren’t you?

Neruda replies, “I am.”

The senator responds, “Good, because two months ago, your name was Ricardo Reyes. Why did you change your name? Did you steal something?”

This isn’t a story about Pablo Neruda’s escape from persecution at the hands of an overreaching Chilean government. This is a story about the creation of a hero.

With incredibly powerful and evocative technique, Larrain shows us that Pablo Neruda was in control of every facet of his legend. When Neruda finds out that he is being forced to go underground to hide from the government he proclaims, “I’m not going to hide under a bed. This has to become a wild hunt.” Thus the conductor flicks his baton and the orchestra heeds.

Gael Garcia Bernal worked with Larrain previously on the film, “NO” portraying a non-fictional marketing guru, who led the successful, “NO” campaign, but this time, while Neruda is essentially a biopic, he portrays an entirely fictional character. The hardened, overly serious Oscar Peluchonneau. The implication of this fictional addition to what is advertised as a biopic is stimulating to say the least. What thickens the stew is that Peluchonneau is also our narrator for the entire film. He plays the vital role of grounding the story in reality and perhaps even critiquing Neruda’s legend.

At an orgy-esque party, Neruda dresses up as Lawrence of Arabia and reads poetry to a captivated crowd of loving communist camrades. Peluchonneau comments, “They don’t know what it is to sleep on the floor, but they are all reds.” And in this way, we see the discrepancy between Neruda, the man that won the Nobel Prize and held millions of Chileans captive with his poetry, and the man who is all too aware of his own narrative. The man that represents the aristocracy of Chile while still a hero amongst Chilean Communists. After living in hiding for merely days Neruda’s wife Delia Del Carril complains about the dishwashing soap making her hands dry. She goes on, “Hygiene is a bourgeois value”

And Neruda bookends, “If we don’t clean, it’s for political reasons.”

Neruda actively works to alter the way that he is perceived from the others, but the hero worship that created Neruda is undercut by the fascist apologist Peluchonneau.

While in hiding, a fellow communist tasked with protecting Neruda brings him novels to read. Stories of crime and police. Neruda tells him, “Police novels help me forget that the police are after me."

And Peluchonneau echoes the truth that’s all too human, “No one can forget that.”

This creates a communist v fascist dialogue via voice over and on-screen conversation that is able to dig more vigorously at Neruda as a legendary figure than what could be accomplished simply by critically examining his actions (the allegedly contrived, legend building actions). While Neruda plays Neruda, Peluchonneau reminds us that he’s playing that role.

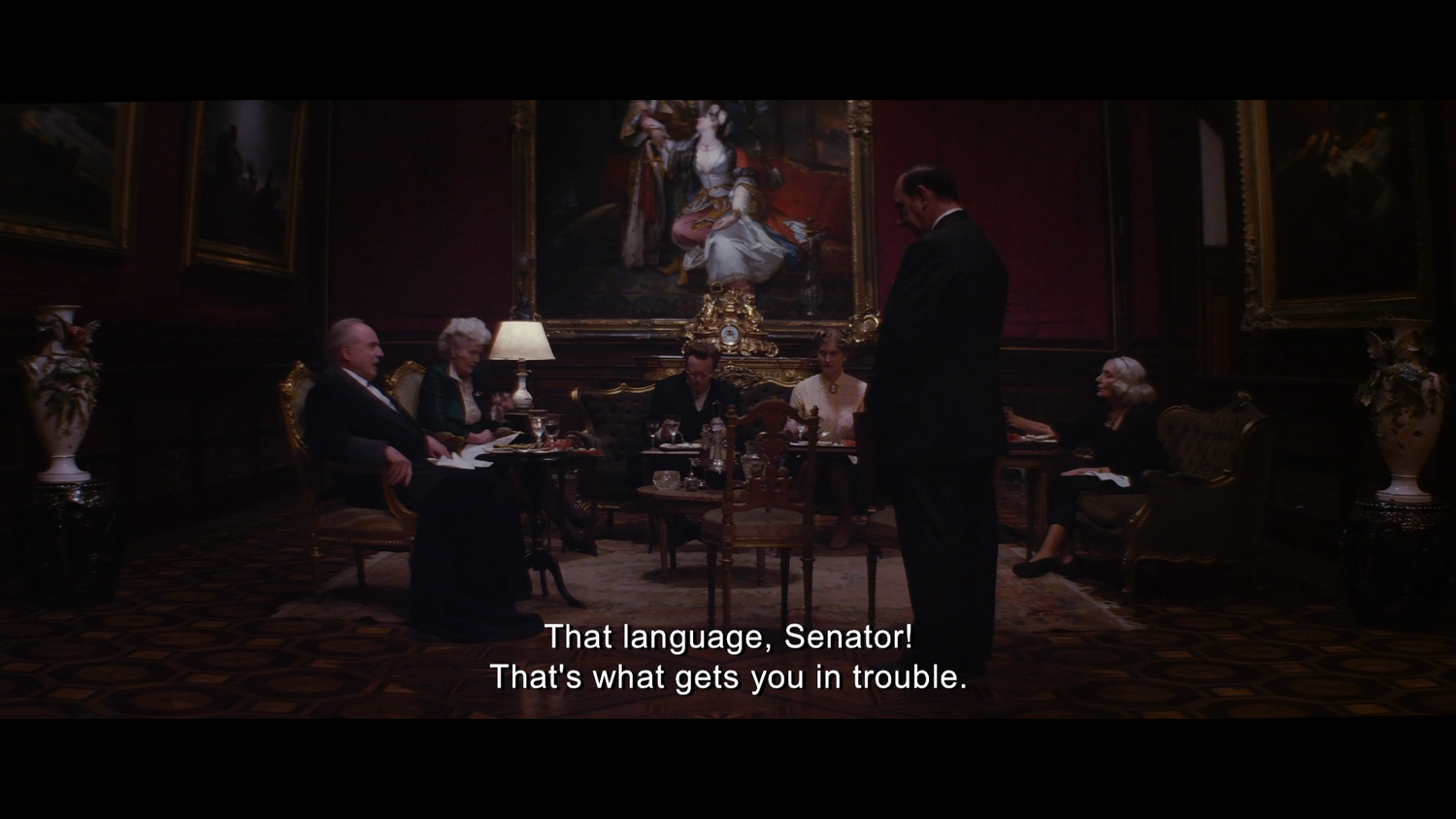

However, what can’t be lost in all of this is Larrain’s absolute disregard for, “reality” in search of, “truth.” In both of his biographical films (Neruda and Jackie), Larrain doesn’t work to portray history as it was, but instead seeks to shed himself of the burdens of the veracity of the genre. He doesn’t just stop there though. Larrain fluidly pulls off perhaps the most blatant disregard for verisimilitude I have ever seen by shooting the same dialogue scenes in multiple different locations then cutting them all together. There is no way after watching Neruda’s first dialog with Alessandri, a Chilean patriarch, that you have a sense that any of this actually happened.

I can imagine Pablo Neruda and his fellows changing the details of this story with Alessandri depending on who’s listening. At one time we’d be in the dimly lit Parisian study, the height of aristocracy. While at the other, the two men are merely silhouettes being watched over by pointed ear, nervously pacing Great Danes and then perhaps in an empty, silent and dark senate chamber. These interwoven narratives emphasize our ability to change ordinary men into legends and heroes. It transforms the film from a simple biopic to a film that’s begging the audience to critique their own perceptions of historic, “heroes.” And in so doing tells the story of a man that has a clenched, white knuckled fist firmly on his own narrative.

When Truffaut wrote his essay in 1954, it was (in my opinion) created out of a sort of goal-centric hubris. That is, Truffaut and his French New Wave colleagues felt compelled to create film that was visceral; film that came from within. They didn’t feel that directors at the time were expressing emotion or thought in a genuine way and so this essay is a reflection on and of what they sought to do themselves.

However, I believe that Truffaut’s assertion is rather myopic, and something that can’t be demonstrated unless it’s a story told by one man. And only if that story told by that one man was told with completely self-aware action—with an intended goal.

Before the French New Wave there were few men that understood the ability to subjectively communicate history better than Pablo Picasso (who just happened to be the man that secured Neruda’s passage to Paris during political exile). In 1937, Picasso completed Guernica and it would be foolish of me to try and describe it’s impact on the artistic community. Guernica is a convoluted, abstract and unsettling masterpiece. Picasso was able to tap into something that crosses thousands of years of story telling and humanity. Perception is truth.

In Guernica, the figures convey a feeling and a thought, rather than specific history and the burdens it brings. His complete disregard for fact, for color, for character, for any semblance of accuracy in the search of truth is what made Picasso, Picasso.

And when I say Picasso, I mean, our idea of who Picasso was, and probably not who he really was.

When trying to flee Chile to Argentina, Neruda is stopped at the border by an agent looking for passports. They hand them over and wait in the car while he inspects them. Finding a discrepancy between the passports and his records, he says to Neruda, “It says here your name is Ricardo Reyes Basoalto.”

Neruda responds, “And my passport reads Pablo Neruda.”

Confused, the agent replies, “But it says, ‘Reyes’ here.”

Neruda’s wife comes to his defense and says, “Because ‘Neruda’ is his artistic name.”

Bret Hoy is the creator and co-editor of Monolith Medium, an award-winning filmmaker, and writer.